Society: AGA

Background: The 2021 ACG Guidelines suggested an infusion of intravenous (IV) erythromycin before endoscopy in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) as it improved gastric visualization during endoscopy and reduced in need for repeat endoscopy. However, IV erythromycin is not widely available. Evidence assessing IV metoclopramide, which is more accessible drug, is scant especially in patient with “active” UGIB. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of metoclopramide for gastric visualization in patients with active UGIB.

Methods: This double-blind, double center, randomized controlled trial study was conducted between April 2021 and October 2022. Patients with active UGIB (defined by either hematemesis or the presence of blood in nasogastric tube) were enrolled. We excluded patients with previous diagnosis of esophageal, duodenal, or gastric cancer or who had a gastric lavage of more than 50 mL. The included patients were randomly assigned to either metoclopramide or placebo in a 1:1 concealed allocation. The primary outcome was clear stomach which defined by endoscopic visualized gastric scores (EVS) 6 or more (total 8). The secondary outcomes included mean difference of EVS, duration of EGD, immediate hemostasis, need for a second look EGD, units of blood transfusion, length of hospital stay, and 30-day rebleeding rate.

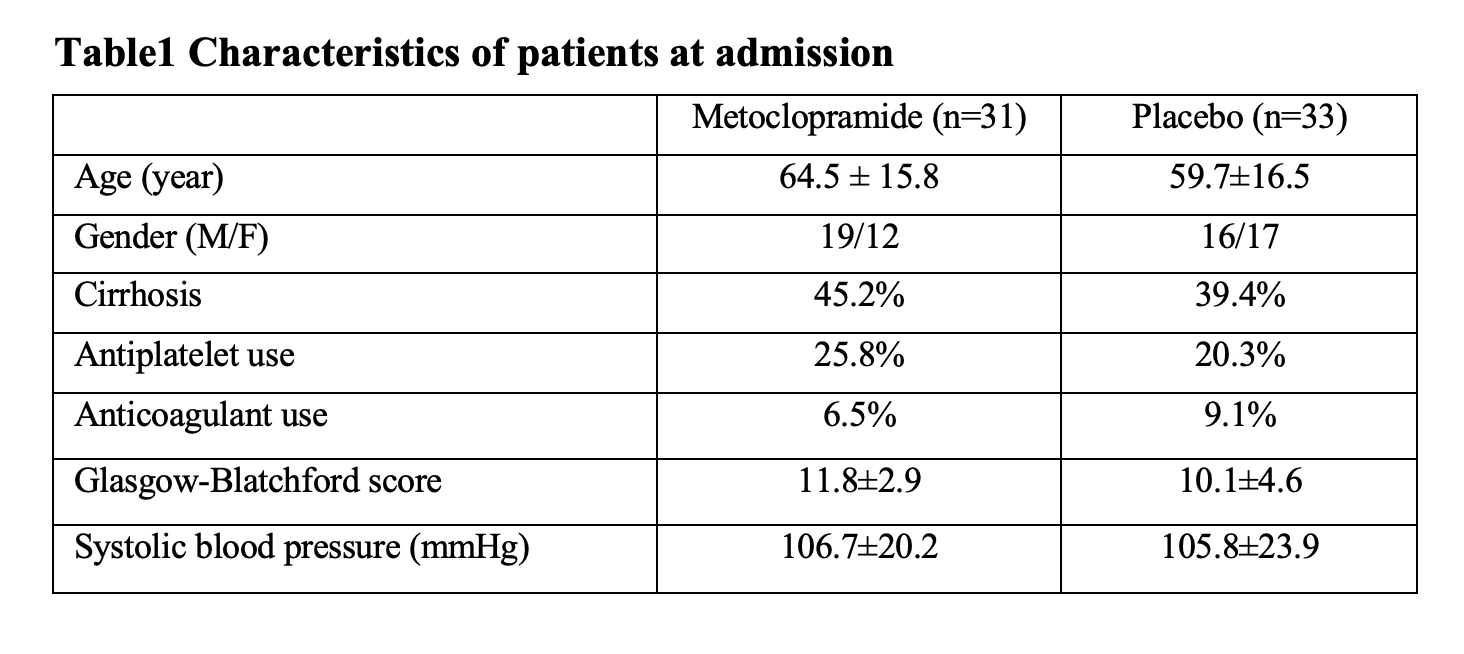

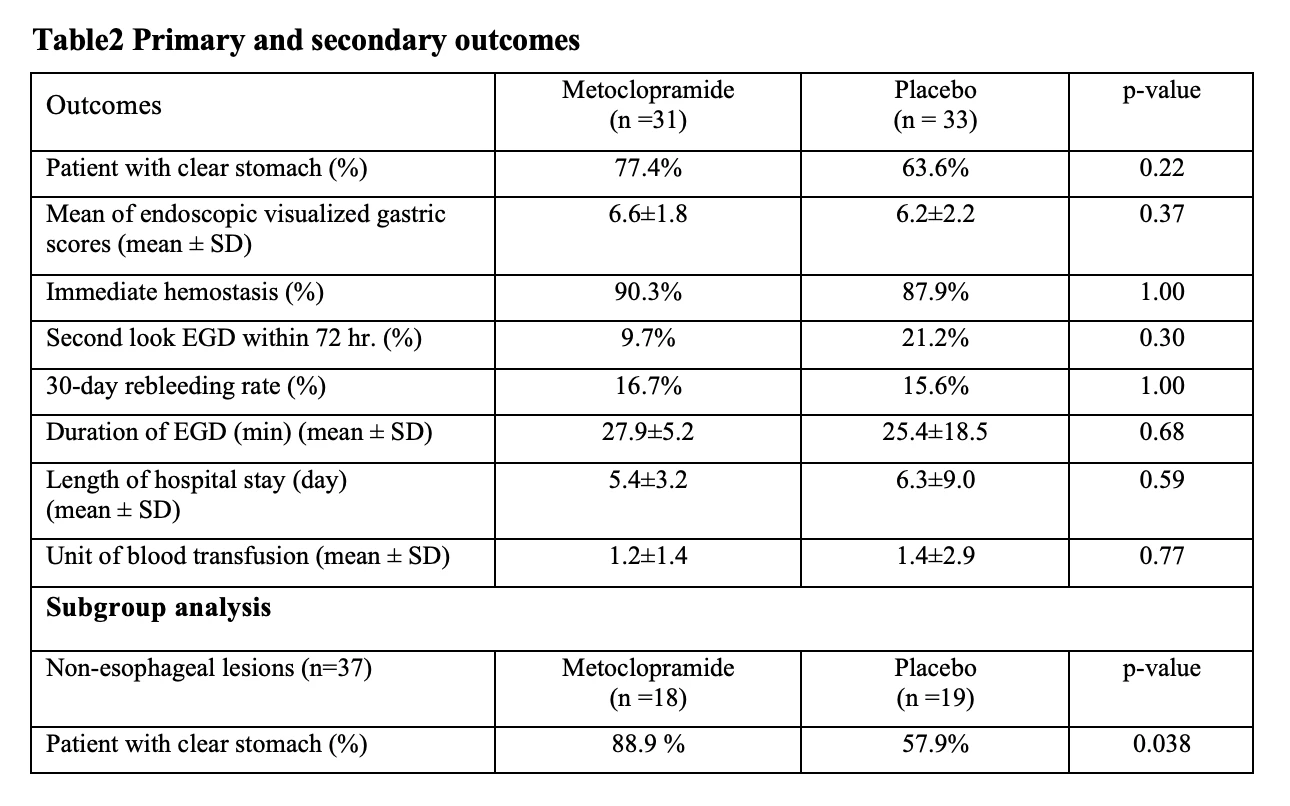

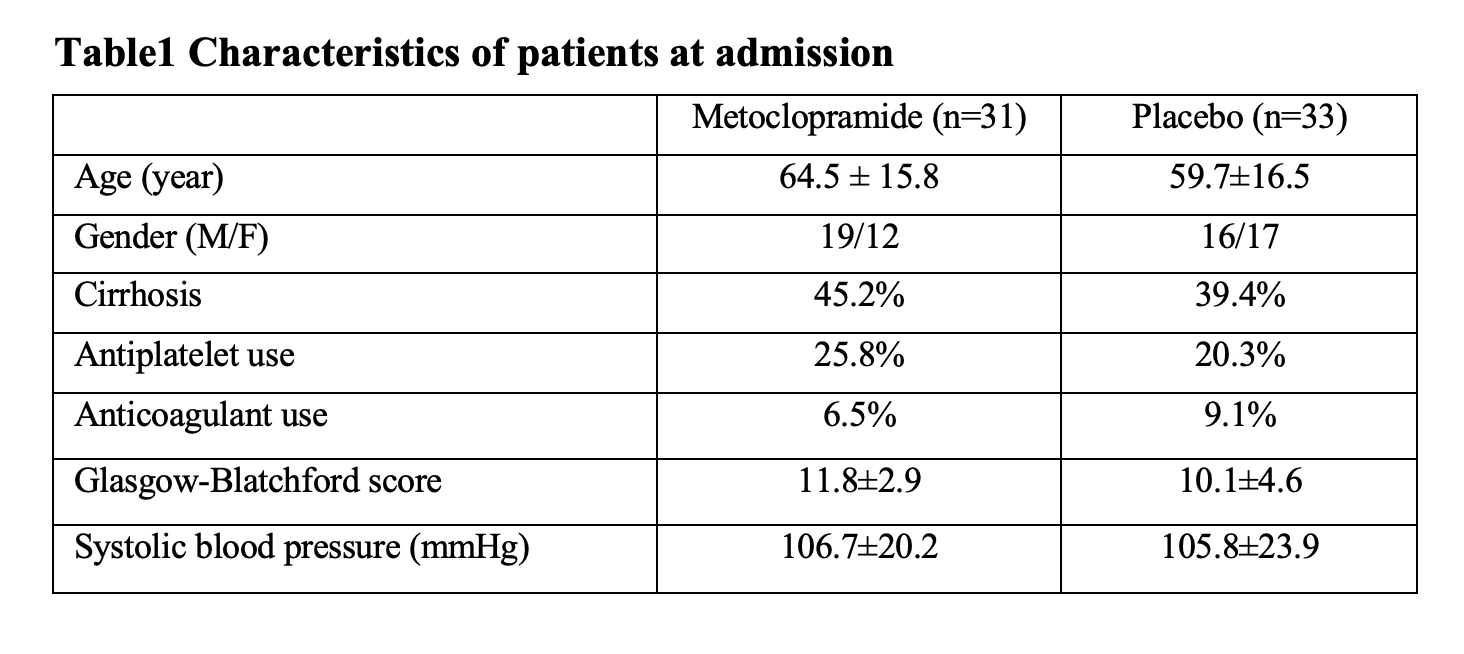

Results: Sixty-eight eligible patients with active UGIB were randomized equally. Then, 4 patients were excluded due to protocol violation. Finally, 64 patients (metoclopramide 31, placebo 33) were analyzed. The baseline characteristics were not different between 2 groups. The Percentage of patient with clear stomach in the metoclopramide and placebo group was 77.4 % and 63.6% (p=0.22), respectively. The mean EVS was not different between two groups (6.6 vs 6.2, mean difference -0.4; p=0.37). The other secondary outcomes were not different between two assigned groups. In non-esophageal lesions subgroup analysis, the percentage of patient with clear stomach was significantly higher in metoclopramide compared to placebo group (88.9 % vs 57.9%, p=0.038)

Conclusion: Metoclopramide did not improve endoscopic gastric visualization in overall active UGIB lesions but significantly increased the clear stomach rate of those patients with non-esophageal lesions.

Table1 Characteristics of patients at admission

Table2 Primary and secondary outcomes

Introduction

Among patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) who take aspirin, management of aspirin at the time of UGIB poses challenges. In a small randomized controlled trial, aspirin continuation in patients with UGIB increased recurrent UGIB risk but decreased mortality vs placebo. Overall, data related to aspirin management in the setting of UGIB are sparse. In a retrospective study, we characterized clinical practice patterns of aspirin management at the time of UGIB, and ascertained the risks of recurrent UGIB, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) [myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA)] or death depending on aspirin management.

Methods

We identified patients admitted for non-variceal, non-cirrhotic UGIB who were taking aspirin at our academic center from 2008-2022. We explored patterns of aspirin resumption (0-3d, 4-14d, 15-60d, and >60d/never). We contrasted aspirin management patterns among patients on aspirin for primary vs secondary prevention (defined by past MI, stroke or TIA). Outcomes were recurrent UGIB, MACE, or death within 60d. Pairwise comparisons between groups were performed using high-dimensional propensity score matching (hdPSM) and logistic regression.

Results

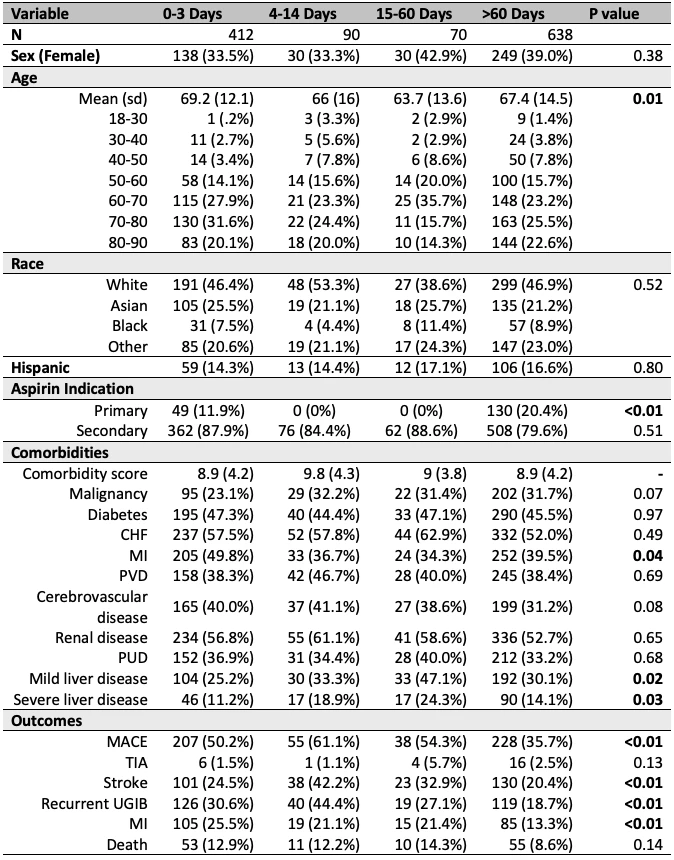

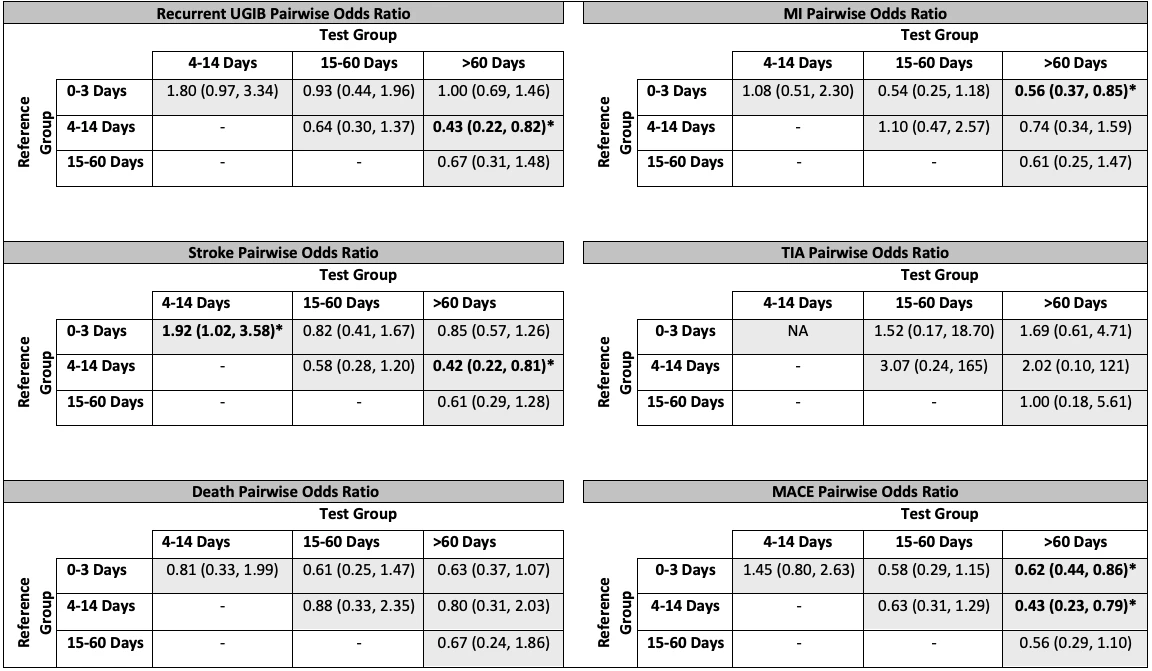

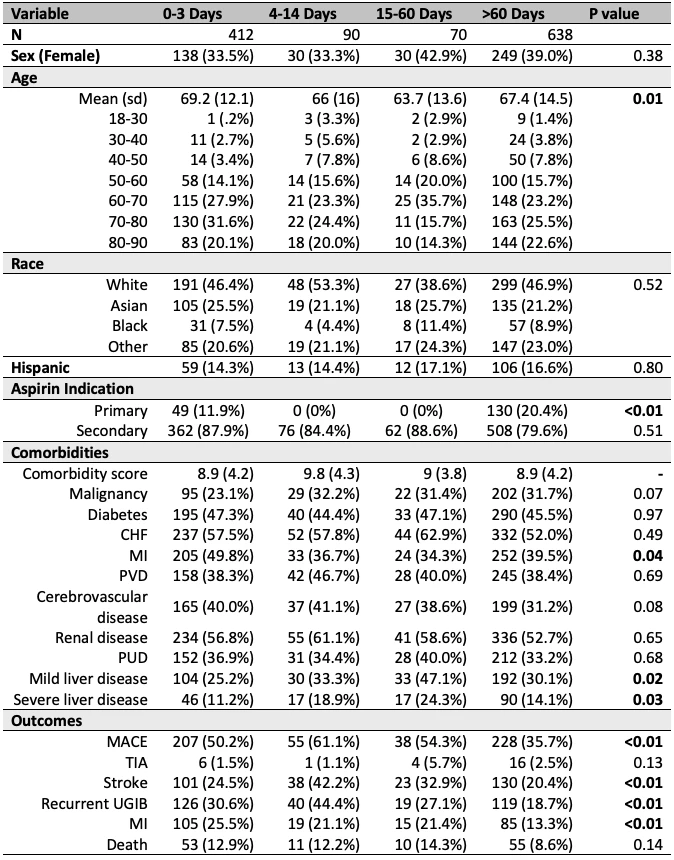

Among 1210 patients, 34% restarted aspirin within 0-3d, 7% within 4-14d, 6% within 15-60d, and 53% >60d/never (Table 1). Patients resuming aspirin within 0-3d were more likely to have history of MI (p=0.01) or CVA (p=0.02) (i.e., secondary prevention), and less likely to have malignancy (p=0.01) vs patients restarting aspirin >60d/never. Among patients taking aspirin for primary prevention, 73% had their aspirin restarted at >60d/never. Among patients taking secondary prevention aspirin, 36% had their aspirin restarted within 0-3d and 50% at >60d/never. The odds for recurrent UGIB were lower when aspirin was resumed >60d/never vs 4-14d (OR 0.43 [0.22-0.82]). Risk for MACE was lower with aspirin resumption at >60d/never vs 0-3d (OR 0.62 [0.44-0.86]) or 4-14d (OR 0.43 [0.23-0.79]) (Table 2). There were no differences in rates of TIA or death (Table 2) as a function of aspirin resumption timing.

Discussion

Among patients with UGIB taking aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention, only 1/3 resumed aspirin promptly, and 50% did not resume aspirin within 60d. This practice pattern deviates from recently published guidelines regarding secondary cardiovascular prevention during GIB. Our observed outcomes are not consistent with those of prior studies and were counterintuitive. These results suggest that despite hdPSM, unmeasured confounders probably exist. Baseline differences in history of MI suggest aspirin management may have been guided by clinical judgment regarding individual patient risk for GIB vs. CV complications. Future prospective research is needed to personalize aspirin management at the time of UGIB.

Table 1

P-values calculated using chi-squared test. CHF, congestive heart failure; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; PUD, peptic ulcer disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; UGIB, upper gastrointestinal bleed.

Table 2

Pairwise comparisons between various aspirin resumption times. Odds ratios calculated using high-dimensional propensity score matching and logistic regression. MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; TIA, transient ischemic attack; UGIB, upper gastrointestinal bleed.